Published: November 8, 2024

By: Alison Lang, UTL News

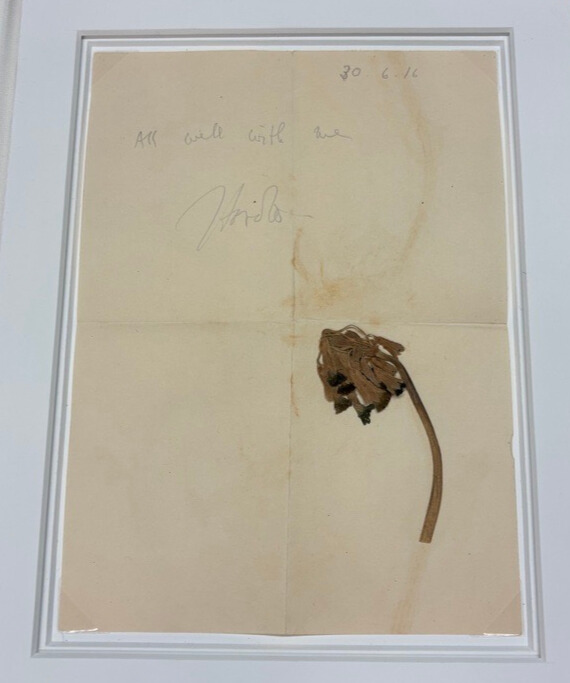

“All well with me.”

It’s a single line, written quickly on a sheet of paper, dated June 30, 1916. Its sender signed his name in a hasty scribble – “Harold.” Contained within its folds is a delicate flower, browned with age, but still otherwise intact.

The letter writer was Harold Wrong, a University of Toronto graduate who was studying at Oxford University when he enlisted in the Lancashire Fusiliers during the First World War. Wrong mailed the letter and enclosed flower to his brother Murray from his post at the Somme in Thiepval, France. It would prove to be the last time he communicated with his family.

The following day, July 1, marked the beginning of the Battle of the Somme, where over 24,000 Canadians were killed. Harold was last seen going over the top of the trenches with a wounded arm. He was never found again, and his brother received his final note – and the plucked flower - days later.

The following day, July 1, marked the beginning of the Battle of the Somme, where over 24,000 Canadians were killed. Harold was last seen going over the top of the trenches with a wounded arm. He was never found again, and his brother received his final note – and the plucked flower - days later.

Until recently, this letter - with its simple, enigmatic message and tragic backstory - was the source of an over 100-year-old mystery: what type of flower did Harold pick to send to his family in his final note?

Now, thanks to the collaborative efforts and detective work of U of T librarians, archivists, scholars and botanists, the heartbreaking mystery of the Somme flower has at long last been solved.

The mystery of the Somme letter

Wrong’s letter is a treasured object at the U of T archives. The letter arrived at U of T’s special collections in the 1960s as part of a package of items gathered from his notable family– Wrong was the son of prominent U of T history Professor George Wrong and the grandson of Edward Blake, the second premier of Ontario and a U of T chancellor.

Over the years, the identity of the pressed flower has remained a continual source of fascination, particularly for Loryl MacDonald, associate Chief Librarian for Special Collections and director of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

“In academia, we’re always curious and we always want to know things,” she says. “And to think that a pressed flower like that is 108 years old and survived that long! And the fact that it’s basically Harold’s last letter, trying to assure his family – or maybe assuring himself – that all will be fine…and he doesn’t make it. The fact that the family had preserved the flower for so long is very touching.”

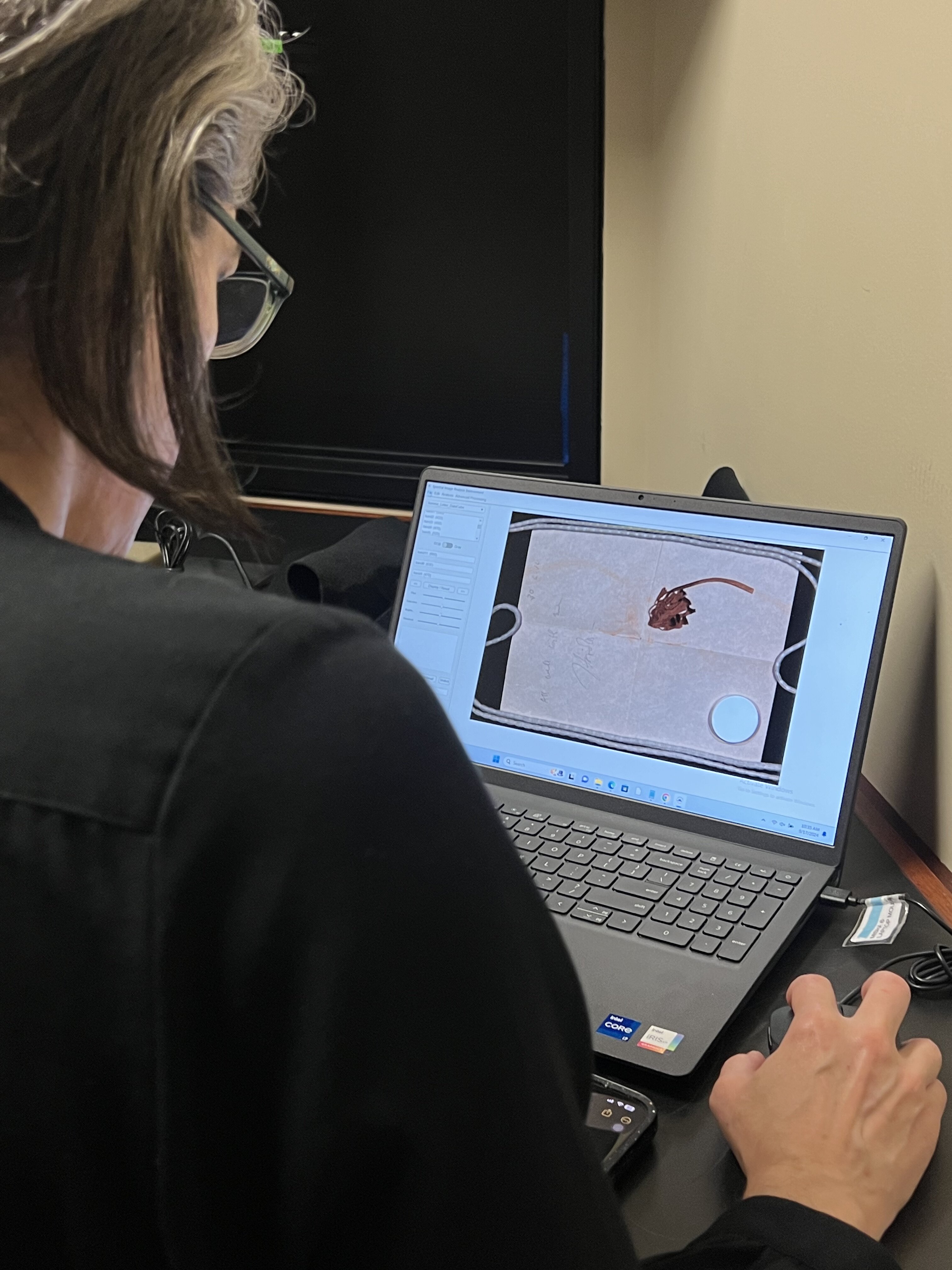

To seek out some answers, MacDonald turned to a new team based out of the Fisher Library in early September 2024. This is the home base of the Mark Andrews Project, where a small team have been using a scanner known as a MISHA (Multi-spectral Imaging System for the Humanities and Archives) to photograph and analyze over a dozen rare and archival materials in the Fishers’ collections. In doing so, they’ve uncovered incredible new details, working with scholars, librarians, and archivists to uncover more of the hidden stories behind these precious documents.

The work with the MISHA is part of an overall collaboration with the Fisher and U of T’s Old Books New Science lab. Longtime Friend of the Fisher Mark Andrews recently provided a generous gift to support this ongoing research, including work by the Andrews Fellow in Book Science, Dr. Stephanie Lahey. As the Somme flower was one of the first items to be scanned with the MISHA, Lahey knew the process might have some logistical challenges. She devised an approach to carefully handle and scan the delicate 100-year-old artifact.

“We had to unfold the letter and get it set up under the camera in a way that wouldn’t move the flower too much, or dislodge it,” Lahey recalls. “We ended up gently flipping over the letter with the flower still attached - at the end of the day, it came through unscathed.”

The MISHA scan was able to identify a couple of key features about the Somme letter and flower – namely, providing a closer look at its blooms and confirming the broken-off stem. However, Lahey knew that confirming the identity of the flower was beyond the MISHA’s capabilities and additional connections would be required.

The Somme letter and flower came back to Dr. Jessica Lockhart, head of research at the Old Books New Science lab, for the next steps. Lockhart found herself getting equally fascinated by Wrong’s letter and set into motion a deep-dive of research and cross-collaborative outreach to find the answers.

“People may ask – why does it matter what type of flower it was?” Lockhart says. “And we’ve said – well, if you know the flower, you know more about Harold. You understand why he found it beautiful and why he wanted to share it. And that’s an important detail that tells us so much more about his final message.”

Going down the research rabbit hole

At the start of her search, Lockhart pivoted back to more traditional research methods using primary sources, including a 1917 account of the Somme battlefield written by Sir Arthur William Hill, the then-director of The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in London, England. “(Hill) had been commissioned to advise on war grave planting,” Lockhart recalls. “So his description was a quick play by play of what he saw, and how the landscape had been changed by the bombing. It’s a very moving piece.”

In his article, Hill painted a starkly evocative picture of a ravaged wasteland – but one in which some plant life still managed to survive. He wrote: “A tree in leaf and only slightly injured may be seen, all the more pathetic and mournful in its loneliness especially when surrounded by gaunt and blackened stems, whose shattered, arm-like branches seem to be pointing with the hand of fate.”

At the end of Hill’s article, he provides a list of 20 plants he observed in his two visits to the battlefield. Lockhart took the list and began to cross check it against the Somme flower – but there didn’t seem to be a match. She then began closely examining archival images from the Somme battle, particularly from Thiepval. Although she couldn’t find a match in the images, she was struck by what she saw. “You never really notice the flowers in these pictures, but there are lots of them,” she says. “In these hellscapes of mud, there are still these living things that managed to survive.”

Lockhart then employed a time-honoured tactic to track down tricky information – she reached out to friends and former colleagues for help. One of these people was Lockhart’s former thesis supervisor Professor Helen Cooper, a medievalist scholar based at Cambridge University, as well as an avid gardener and an expert on English flora and fauna. She identified the flower easily; a blue cowslip. Lockhart was convinced: “It was a shot in the dark – but she’s the kind of person who would know,” she says.

While the anecdotal evidence steered the team in the right direction, there was still one last step to be certain – one that once again required the use of emerging technologies. Cooper recommended that Lockhart consult Plant.net, a site where users can upload images of plants, and an AI-generated algorithm generates possible matches. Lockhart uploaded the MISHA-generated images of the flower with fingers crossed – and the blue cowslip was the clear winner.

A century-old mystery solved

For Lockhart, the journey that led to the solving the mystery of the Somme flower is a perfect example of the collaborative and experimental nature of book science work – employing new and emerging technologies, scholarly skills and even the lived experience of experts across disciplines.

“We can always use the tools at our disposal, but finding out these kinds of answers will always be an interdisciplinary and group exercise,” she says. “This is what book science should be – helping to uncover the parts of the story that have been lost and connecting people with the right experts to find the answers. I hope this is the kind of thing we can keep doing with the Fisher going forward…this feels like the right thing for us to be doing.”

“We can always use the tools at our disposal, but finding out these kinds of answers will always be an interdisciplinary and group exercise,” she says. “This is what book science should be – helping to uncover the parts of the story that have been lost and connecting people with the right experts to find the answers. I hope this is the kind of thing we can keep doing with the Fisher going forward…this feels like the right thing for us to be doing.”

For MacDonald, the emotional resonance of the discovery is profound. The identity of the flower creates a powerful new angle through which to view the Wrong letter, its place in Canadian war history, and what Wrong was thinking about on that fateful afternoon. Against a backdrop of so many lives lost in war, the Somme flower has somehow survived all these years – and now it will continue to live on.

“If this is indeed a blue cowslip, they typically only bloom in spring, and Wrong would have seen it around June 30th, which is even more poignant,” MacDonald says. “Harold’s attention was likely drawn to it because it was still in bloom in late June.”

“There is symbolism here. It’s often said that the First World War plucked a generation of youth, and perhaps that is what that flower symbolizes too – a beautiful and rare thing that Harold plucked as his final message to his family. I think that’s what’s been most important to me about this discovery.”