Published February 13th, 2025

by: Alison Lang, UTL News

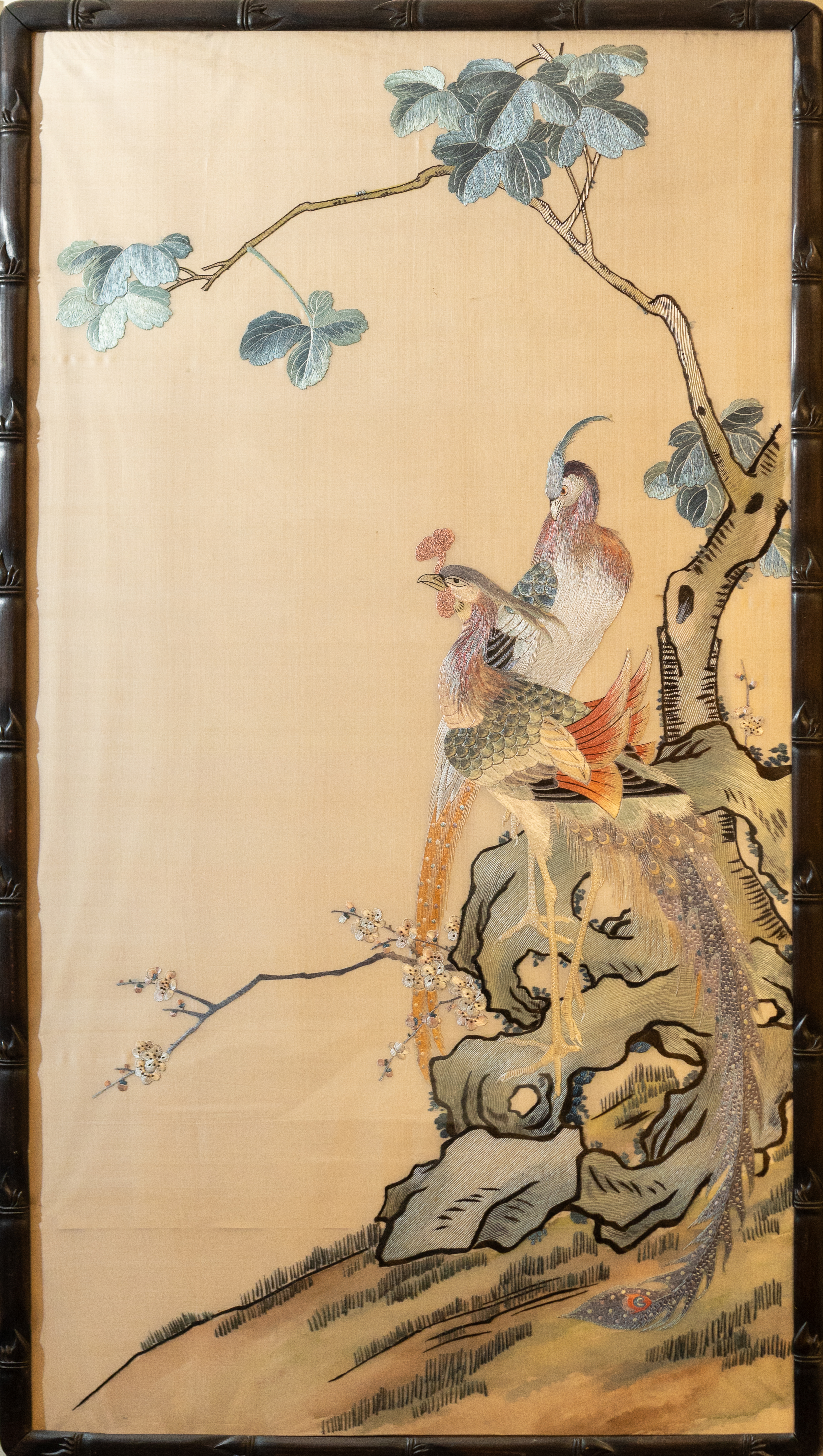

Among the many significant and beautiful works of art in the holdings of the Cheng Yu Tung East Asian Library (EAL), there’s one piece in particular with a very special story. It is a three-panel embroidery artwork in the style of Chinese painting, adorned with calligraphy characters and a beautifully embroidered image of two birds sitting on a hillside.

Created by an unknown artist, the panels were gifted to Rosy Muriel Wing and Steven Benny Chan on their wedding day on August 8th, 1932 in Victoria, B.C. The panels are significant for a few reasons – they feature Chinese embroidery, a centuries-old rich and complex artistic practice that was often passed down through families.

The gift also represents the larger significance of the Chan wedding, which was a rare occasion for a Chinese couple who were both born in Canada (Rosy in Vancouver, and Steven in Victoria). The fact that the couple married during the height of the Exclusion Era (July 1, 1923 to January 1, 1947), is also notable – it marks a long period of anti-Asian discrimination, when Chinese immigrants were excluded from Canada, and economic opportunities for Chinese people in the United States and Canada were severely limited due to government prohibitions. With all this in mind, a celebratory wedding likely held even greater meaning.

Rosy Wing and Steven Chan’s son and daughter-in-law, Dr. Anthony Chan and Dr. Wei Djao, inherited the panels in 2000. As longtime friends and supporters of the EAL, the Chan family generously donated them to the library in 2010.

On the eve of Valentine’s Day, UTL News spoke with Dr. Djao about the panels, their importance to Dr. Chan, who passed away in 2018, and how the art speaks for generations of their family.

Can you tell me the story of how these panels came to Canada?

These panels were a wedding gift to Dr. Anthony (Tony) Chan’s parents. They got married in 1932. That gift came from his maternal grandfather Koo Kai Tak in Hong Kong. It is interesting because this was the Chinese custom at this time – people would congratulate the bridegroom’s parents rather than directly congratulating him, or the bride. So these panels were actually addressed to Tony’s grandfather Chan Wing Dun. Today people may still send gifts like this, but it’s much more likely to be addressed to the newlyweds.

Tony’s father was born in Victoria and his mother was born in Vancouver. There were not a lot of Chinese people in B.C. during that time, so it was an arranged marriage – there was a professional matchmaker who likely introduced the two families to each other. That’s how it was at that time. Even before the Exclusion Act was passed into law, it was the practice not to allow Chinese people into Canada. So the wedding was quite an important occasion.

Do you know how the panels were made?

I don’t know the full story. It was probably more common in those days to send this type of gift. It’s not exactly the case that you would find these on every street corner, but there were more people making this type of art. Initially I thought all the calligraphy was done in ink. I have to say it’s only after a couple of years that I took another look and realized everything is embroidered! It is quite remarkable. The artist would have done the calligraphy first, and then a skilled embroiderer (most likely a woman) would have embroidered on top of it. I don’t think you’d be able to find this type of work easily today – if you really searched, you might find people making embroidery art, but it would be quite expensive.

I can tell someone spent a lot of time working on these panels - it’s very painstaking.

Can you tell me a bit more about the symbolism of the two birds in the centre panel?

The two birds are very common imagery for (Chinese) weddings. It represents the couple – the two birds are ones that mate for life. They will not have another partner, even if one of them dies. The idea with wedding imagery is that the two people will grow old together until “we are both white heads.” In the same way, these two birds will grow old and white-headed together.

The words on the two smaller panels aren’t about the birds, or the wedding at all! The right panel talks about making and drinking tea, from the water of a pure stream, and how the tea will have the flavour of the stream. The second panel talks about poetry. The two panels have nothing to do with marriage. It’s funny, I know.

And yet – if a couple can enjoy the simplicity of life, of tea and poetry together, I think it’s saying that they will have harmony. If you have the time and peace to enjoy tea and poetry, that’s a pretty good life, I think!

How did you and Tony meet?

We met at a conference, I believe in 1979. Later that year, there was a TV program on the W5 channel that marked the beginning of the anti-W5 movement. It was called “Campus Giveaway” meaning that Canadian universities were allegedly giving away the spaces in their programs to non-Canadians, or non-immigrant Chinese people.

At that time there were quite a few landed immigrants – people who are legal residents, who can stay in the country permanently and eventually became citizens. Foreign students were not landed immigrants, and had VISAs that they could re-apply for – but they would eventually leave after their programs were completed. It’s quite a difference. The W5 program had a lot of errors, and depicted a class of pharmacy students who were all landed immigrants or Canadian citizens. So it was wildly incorrect, and it sparked the first time that Chinese Canadians across Canada joined in a movement together.

I was teaching at the University of Saskatchewan and organized a Chinese Canadian protest there against that program. Tony and I were just beginning to see each other. That Christmas I came back to Toronto to visit my family and Tony also came back – partly because of that W5 program, and because of the protests being organized here. So we spent time together as part of that movement in Toronto.

It sounds like your marriage was a romance forged at the same time as one of the biggest Chinese Canadian protests in this country’s history!

(Laughs) We certainly strengthened and fortified our views about Chinese Canadian identity together! And we made plans. It was a very unprecedented time. I came here as an immigrant after finishing high school in Hong Kong. And Tony was really the first generation of Canadian-born Chinese to go to university. I think it may be hard for people today to understand the level of racism against Chinese Canadian people – we were getting good jobs, we were getting into universities, after many years of not being allowed in professional faculties.

When you look at the panels, do they remind you of Tony, or of his family history?

Yes, it does remind me of Tony, and his parents. When I think about the panels, it reminds me of all the generations involved. Since so many of them are deceased, it was a loving way for us to remember them all. When we received the panels after Tony’s father passed away in 1999, we felt they would be much more appropriately kept in an institution. I think Tony was very glad that the panels went to the EAL. I first used the EAL in 1969 as a student and always felt at home there. It has an amazing history and we’re so proud that this family item is part of its legacy. All the users will be able to read and appreciate the calligraphy and see what Tony wrote about the panels. It’s very special for us.